Why We Use Acropora Corals in Our Thailand Restoration Project

If you’ve dived in Thailand and hovered over a coral garden full of branching “staghorn” structures or wide, flat “table” corals, chances are you’ve been looking at Acropora.

These corals are some of the main architects of shallow reefs in the Andaman Sea, including the sites we visit around Phuket and the Similan Islands. They grow quickly, create complex habitat, and build much of the three-dimensional structure that fish and invertebrates depend on.

They’re also some of the first to get hit when things go wrong.

At DiveRACE, Acropora are at the heart of our coral restoration project in Thailand. To understand why we chose them – and why they matter – it helps to look at how they work, piece by piece, from the level of a single coral polyp up to the reef as a whole.

What Exactly Is Acropora?

“Coral” is a big word that covers many different species. Acropora is a genus within the stony corals (Scleractinia), with dozens of species found in Thailand’s waters. Here, you’ll commonly see:

- Thin, branching staghorn corals

- Thicker branching forms

- Wide table corals that form flat plates

Regardless of shape, Acropora colonies share the same basic architecture: they’re made up of thousands of tiny animals called polyps, all connected by living tissue and a shared calcium carbonate skeleton.

These colonies don’t just sit on top of the reef – they build the reef. As they grow and die, their skeletons accumulate, forming the framework that other corals, algae, sponges, and animals colonise over time.

Coral Anatomy 101: How a Tiny Polyp Builds a Reef

To understand why Acropora is so important (and so vulnerable), you need to get familiar with the anatomy of a single coral polyp.

Each polyp is a small, soft-bodied animal related to jellyfish and anemones. It has:

- A cylindrical body anchored in a cup-shaped skeletal structure called a corallite

- A ring of tentacles around a central mouth

- A thin layer of tissue (the coenosarc) that connects it to neighbouring polyps

Beneath the tissue is the calcium carbonate skeleton – the hard part we see when corals die and turn white rock-like. Polyps secrete this skeleton, layer by layer, through a process called calcification. Over time, thousands of polyps building together create the branching and table shapes that Acropora is known for.

Now add one more crucial ingredient: microscopic algae called zooxanthellae living inside the coral’s tissues.

How Corals “Think” About Energy: The Zooxanthellae Partnership

Acropora, like most reef-building corals in Thailand, relies heavily on a symbiotic relationship with zooxanthellae (tiny photosynthetic algae).

The deal is simple but powerful:

- The coral provides the algae with a protected home and access to light.

- The algae, through photosynthesis, produce sugars and other nutrients that feed the coral.

This partnership is why healthy corals tend to live in clear, shallow, sunlit water. Light drives photosynthesis, which drives energy production, which fuels growth and calcification.

Corals can also feed using their tentacles, capturing plankton and organic particles from the water, but for Acropora in clear tropical waters, most of their energy comes from their symbiotic algae.

When water gets too warm or conditions become stressful, this relationship breaks down. The coral expels or loses its zooxanthellae, turns pale or white, and enters what we know as coral bleaching. If conditions don’t improve in time, the coral starves.

How Acropora Survive, Grow, and Reproduce

In Thailand’s reefs, Acropora has evolved to do one thing very well: build complex, shallow-water structure quickly.

They survive and spread using a combination of:

Rapid skeletal growth

Acropora is generally faster-growing than many massive corals (like brain or boulder corals). That speed allows it to colonise open spaces and create branching or plating structures in a relatively short time. The downside: faster-growing species often have thinner skeletons and can be more easily broken by waves, storms, or contact.

Photosynthetic energy from zooxanthellae

In the clear waters of the Andaman Sea, Acropora can use abundant sunlight to drive high rates of photosynthesis. This fuels growth and helps the coral lay down more skeleton.

Asexual fragmentation

Acropora is particularly good at fragmentation. When a branch breaks off – during storms, strong waves, or minor physical disturbance – that piece can settle in a suitable spot, reattach, and continue growing as a new colony. This is exactly the property that makes Acropora so useful for coral restoration projects.

Sexual reproduction and spawning

Like many corals, Acropora also reproduces sexually through broadcast spawning, releasing eggs and sperm into the water column during coordinated events. This creates genetic diversity and allows larvae to settle on new surfaces, but it’s a long-term, less predictable process compared to using fragments.

What Affects Acropora in Thailand’s Reefs?

Once you understand how Acropora functions, it becomes easier to see why it is both critical and at risk in Thailand’s coral reefs.

Several key factors affect its survival:

Temperature and bleaching

Acropora is often among the first to bleach during marine heatwaves. Because it relies heavily on zooxanthellae, elevated sea temperatures can quickly destabilise this relationship. The Andaman Sea has already experienced multiple bleaching events in recent decades, and many Acropora-dominated sites have been hit hard.

Light and water clarity

Too little light (from sediment, algae blooms, or turbid runoff) reduces photosynthesis. Too much suspended sediment can also smother delicate branches and block polyps from feeding properly.

Water chemistry

Like other reef-building corals, Acropora depends on stable pH and carbonate levels to calcify efficiently. Ocean acidification – caused by rising CO₂ levels – can make it harder for corals to build and maintain their skeletons.

Physical damage and breakage

The same branching structure that provides great habitat is also more fragile. Anchors, fishing gear, careless fin kicks, and contact from snorkellers or divers can easily snap Acropora branches. Natural storms do this too – but repeated human-caused breakage adds unnecessary stress. This is where divers and snorkelers should be wary about their posture and fins underwater. Any accidental breakage means decades of growth loss!

Predators and disease

Coral-eating snails (such as Drupella), crown-of-thorns starfish, and various coral diseases can target Acropora colonies. When reefs are already stressed, outbreaks become more damaging.

In many parts of Thailand, all of these pressures stack on top of each other. That’s where coral restoration comes in – not as a magic fix, but as a way to give damaged areas a fighting chance to recover.

Why We Use Acropora in Our Coral Restoration Project

Given that Acropora is so sensitive, you might ask: why choose it for restoration at all?

There are several reasons we deliberately use Acropora fragments in our DiveRACE coral restoration project near Phuket:

It’s a natural dominant species in shallow Thai reefs

We’re not introducing something foreign. Many of the shallow sites in the Andaman Sea are naturally dominated by Acropora. Restoring Acropora helps return the reef toward its original structure and function.

Fast growth means visible, meaningful change

Because Acropora grows relatively quickly, you can see clear progress over months and years. Fragments attached to our reef structures – often welded “star” frames on the seabed – start as small pieces and gradually develop into branching mini-colonies. This creates habitat far faster than if we tried to rely only on slow-growing massive corals.

Fragmentation fits the species’ natural strategy

We are not forcing Acropora to do something unnatural. In the wild, broken branches can and do reattach and grow into new colonies. In our project, we simply guide that process:

- We rescue naturally broken fragments that would otherwise die in unstable rubble.

- We attach them to stable steel structures at suitable depths (for example, 6–10 metres).

- We monitor their survival and growth over time.

Structural complexity benefits marine life quickly

Acropora’s branching and table shapes create immediate three-dimensional structure that fish and invertebrates can use for shelter and feeding. Even before the fragments have fully overgrown the frames, we often see more fish activity at restoration sites simply because there is more structure.

Linking Science to Practice: How Our Restoration Works

On our DiveRACE coral restoration site, we apply all this coral biology in a practical, hands-on way.

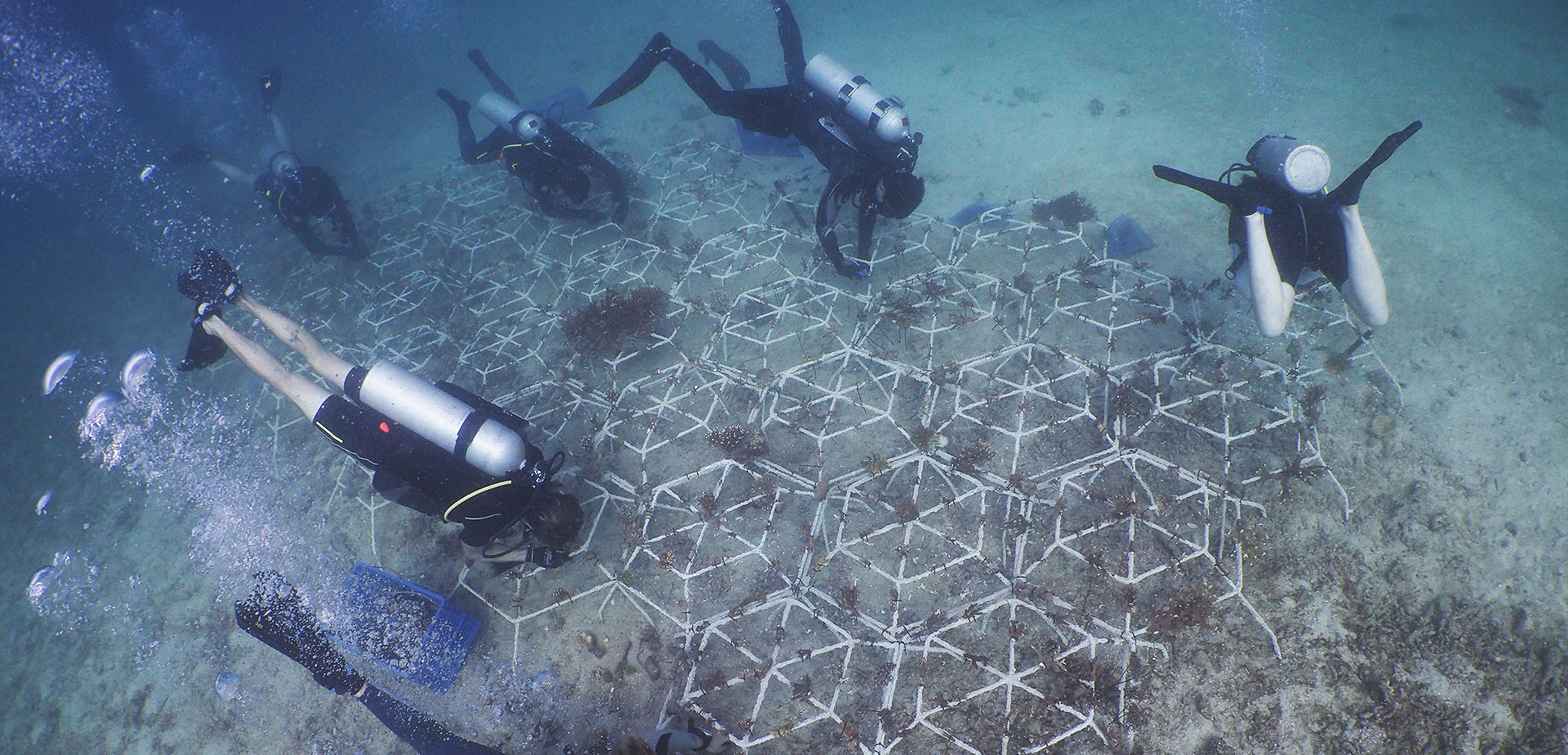

We start by selecting stable seabed areas and installing modular reef structures – often interconnected “reef star” style frames. These lift coral fragments slightly off the bottom, away from shifting sand or rubble, and provide a secure base.

When we collect Acropora fragments, we focus on:

- Healthy pieces already broken off existing colonies

- Species well-suited to the local light, depth, and wave conditions

- Spacing that allows each fragment room to grow without immediate competition

We then attach these fragments to the frames, usually with cable ties or similar fixings that can hold the coral securely until it encrusts and fuses with the structure.

Because we understand how Acropora feeds and grows, we place frames at depths and locations where they receive adequate light, clear water flow, and good water quality. We also know that Acropora is vulnerable to bleaching, so site selection and depth are chosen with those risks in mind, not just for convenience.

Over time, we return to:

- Check for algae overgrowth and remove it when necessary

- Watch for predators like Drupella and manage them if they pose a threat

- Document growth through photos and video

- Replace fragments that didn’t survive so the structure continues to fill in

The result is a living laboratory of how Acropora corals in Thailand respond to carefully managed restoration – rooted in science, but visible to any diver who joins us underwater.

Why This Matters for Divers

Understanding Acropora at the scientific level – from polyps and zooxanthellae to branching colonies and reef frameworks – changes how you see the reef.

You realise that:

- That “bush” of staghorn coral is thousands of tiny mouths, each hosting algae and secreting skeleton around the clock.

- A broken branch is not just a cosmetic issue; it’s a setback for energy capture, growth, and habitat.

- A healthy Acropora thicket is a high-performance solar-powered factory, feeding itself and sheltering an entire food web.

When you join us for diving or coral restoration activities with DiveRACE, you’re not just looking at pretty scenery. You’re visiting a complex biological system that we are actively working to support and rebuild.

By choosing to dive carefully, avoiding contact, controlling your buoyancy, and – if you wish – participating in or supporting our Acropora-based restoration work, you become part of that system’s recovery rather than its decline.

Acropora helped build the reefs that made you fall in love with diving in Thailand. With the right knowledge, and the right restoration approach, we can help them keep building for years to come.

Learn more about our coral project here: https://diverace.com/coral-restoration-project/

Related Articles

-

Climate Change & Corals: How Extreme Weather and Warming Seas Shape Our Reefs

In recent years, Southeast Asia has experienced increasingly unpredictable and severe weather…

-

Corals in Thailand: How You Can Help with DiveRACE

When people talk about scuba diving in Thailand, they almost always mention…

-

Acropora Corals in Thailand: The Science Behind Our Restoration Work

Why We Use Acropora Corals in Our Thailand Restoration Project If you’ve…